Nobel Prize winner Professor Robin Warren, one of the Aussie scientists who famously discovered what H. pylori bacteria did to the stomach, has died.

Nobel Laureate Emeritus Professor (John) Robin Warren AC, one of two Australians credited with discovering that most peptic ulcers are an infectious disease caused by the bacteria Helicobacter pylori, has died at the age of 87.

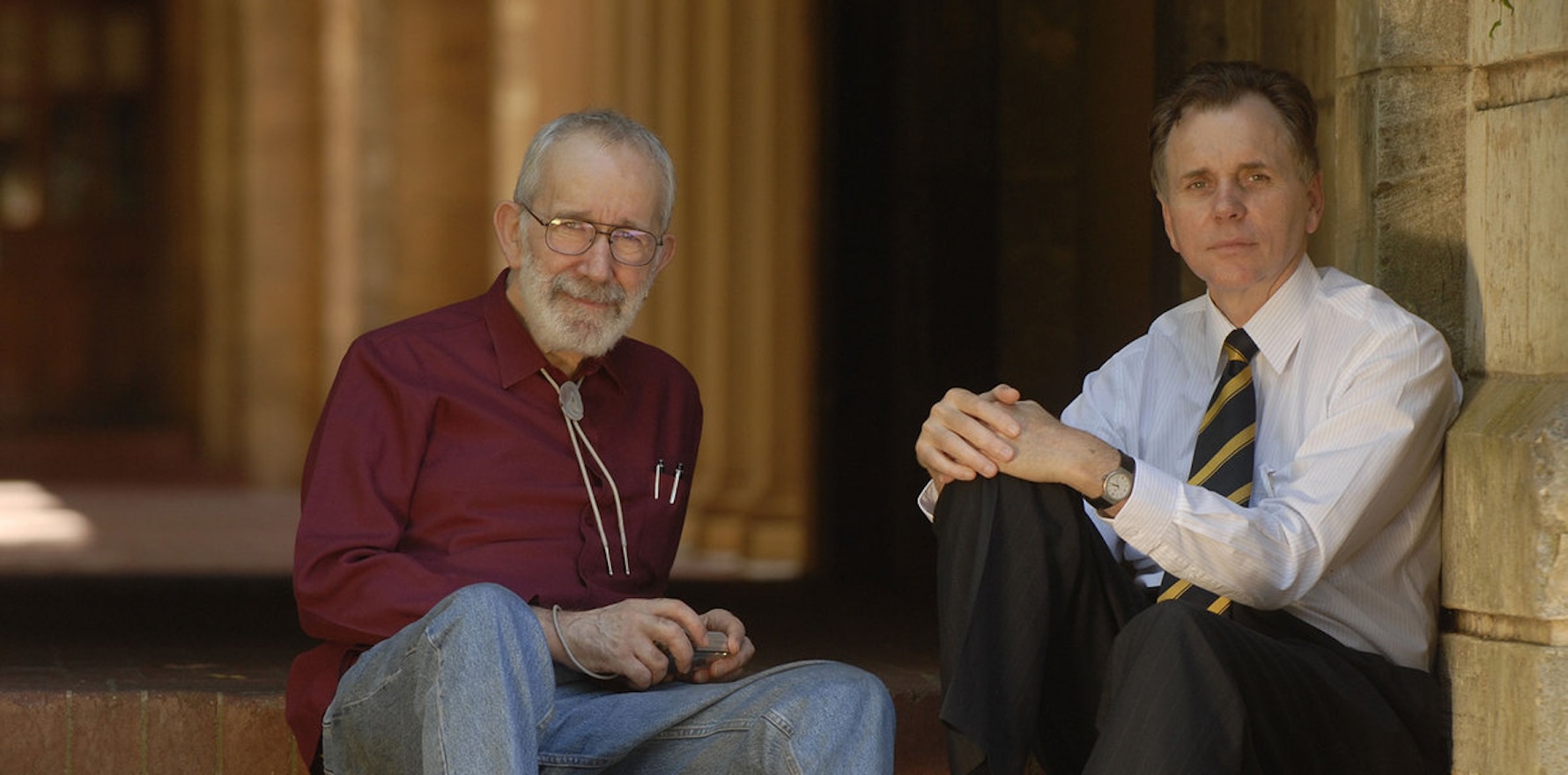

His controversial work with gastroenterologist Professor Barry Marshall earned then a join Nobel Prize in 2005. They were also joint winners of Western Australia’s Australian of the Year award in 2007, and also received Australia’s highest civilian honour, the Companion of the Order of Australia (AC).

Professor Warren died this week in Perth. Professor Marshall told Gut Republic that his former research partner and friend of more than 40 years had been ill for a while. He died peacefully surrounded by his family.

Professor Marshall said Professor Warren would be well remembered for the impact their research had on significantly decreasing the incidence of ulcers, stomach cancer and beyond.

“In countries where stomach cancer is common, if you get rid of it, you free up a lot of gastroenterologists and medical resources to go into other things, and the other thing is probably going to be colon cancer as we get older,” he said.

“One of the reasons that Australia’s got a lowering incidence of colon cancer is because the gastroenterologists have got a bit more free time to do colonoscopies and do screening and things like that.

“So indirectly, Dr Warren and I have had a big impact on curing, preventing and curing colon cancer.”

The H. pylori work done by Professor Warren and Professor Marshall revolutionised the treatment of gastro-duodenal ulcers, by enabling an antibiotic cure, and has led to a significant reduction worldwide in the prevalence of gastric cancer.

Professor Marshall remembered their first meeting in 1981 when he was a young clinical fellow.

“I came in contact with Dr Warren at pathology meetings and occasionally he would mention these bacteria and the surgeons would be saying ‘ha ha ha, Robin’s talking about his bacteria again’,” he told GR.

“So when, when I got the chance to work with him, I was pretty interested. And he convinced me, he just showed me all this microscope stuff. And I said, you know, I believe it. Let’s go find out where they come from. And one thing led to another.”

University of Western Australia Vice-Chancellor Professor Amit Chakma said the university extended its condolences to the Warren family and his friends and colleagues.

“Our university is very proud of Robin Warren and the difference that he and Barry Marshall’s research has made to the lives of millions of people around the world,” said Professor Chakma.

“Robin was a medical pioneer and along with Barry, he defied his detractors, dedicating himself to prove a theory that resulted in greater global health outcomes.”

UWA renamed its medical library the J. Robin Warren Library in 2017, acknowledging his past impact as well as future inspiration to students working and studying in an educational facility named in his honour.

Robin Warren Drive, where Fiona Stanley Hospital is located, was also named in his honour.

AMA (WA) president and pathologist Dr Michael Page acknowledged the significant contributions of Professor Warren, who was also a recipient of the AMA (WA) Hippocrates Award.

“Professor Warren was a giant of pathology and medicine more broadly; a Nobel-prize winner who, with gastroenterologist Professor Barry Marshall, made a discovery that transformed the way we understand, diagnose and manage peptic ulcer disease,” he said.

“I extend my condolences to Professor Warren’s family, friends and colleagues.”

Born in Adelaide, Professor Warren graduated in 1961 with a degree in medicine from the University of Adelaide before becoming a pathologist. He took up a pathology position at Royal Perth Hospital in 1968 where spent most of his career.

Professor Warren told his life story in his Nobel Prize biography, detailing his childhood days in Adelaide to arriving in Perth in 1968 – just a few years before the fuse was lit for his foray into research on H. pylori.

“During the 1970s, I wrote up a few interesting cases and developed an interest in the new gastric biopsies that were becoming frequent. I also attempted to develop improved bacterial stains for use with histological sections, as I describe more completely in my Nobel lecture,” he wrote.

“Then, in 1979, on my 42nd birthday, I noticed bacteria growing on the surface of a gastric biopsy. From then on, my spare time was largely centred on the study of these bacteria. Over the next two years, I collected numerous examples and showed that they were usually related to chronic gastritis, usually with the active change described by Richard Whitehead in 1972.

“I attempted, with some difficulty, to obtain a negative control series, by collecting cases reported as normal gastric biopsies. This was more difficult than I expected, because all gastric biopsies were coded the same, wherever they came from in the stomach.

“Almost all so-called normal biopsies were from the corpus. Normal biopsies from the gastric antrum were very rare, but I eventually found 20 examples, and none showed the bacteria. With this material available, I began to prepare a paper for publication.”

In 1981, he met Barry Marshall when they were both working at Royal Perth Hospital, beginning what was to become a legendary partnership.

“By 1990, our findings began to be recognised by the medical community,” Professor Warren wrote.

“We started to receive increasing numbers of honours and requests for attendances at meetings and lectures. It had been an interesting decade. After our initial publications in 1983–84 [including this one in the Lancet, which would be their most famous], a wealth of further studies appeared, most of them apparently just repeating our work, with similar results.

“No one proved we were wrong. Yet in spite of this, no one but patients and local general practitioners appeared to believe our findings. Many patients demanded treatment, and some GPs were very keen to treat them. Otherwise, it seemed that only our wives stood beside us.”

In one of their most famous experiments – published in 1985 in the Medical Journal of Australia – Professor Marshall drank a broth containing H. pylori. It remains one of journal’s most cited articles even today.

Within a week Professor Marshall was experiencing pain and other symptoms of acute gastritis, which were confirmed by stomach biopsies to be due to H. pylori infection. A course of antibiotics cured his condition.

Professor Marshall remembers them discussing the experiment.

“I said, ‘look, we’ve tried to infect pigs for six months, but that is not working as pigs are immune to these bacteria. We’re going to have to get a human volunteer. [I said], Robin, I think it should be you. He says, no, no, no, I’ve already had helicobacter once, so I might be immune. So, Barry, I think it has to be you’,” he said.

“We did have this plan that if the animal research failed, we would need human volunteers, and I was thinking medical students [until they decided to conduct the experiment on him].

“Things were moving along rather slowly, and it was a big stumbling block, because we could not prove that healthy people could be infected with this germ.”

Their leap of faith made medical history.

“We didn’t have a good treatment for these bacteria until about the year 2000 and then we practically eliminated the disorder of ulcers in Australia,” Professor Marshall told GR.

“They’re [ulcers] pretty rare these days, whereas it used to be that, you know, everybody kind of knew someone who had an ulcer, and you’d be expected to retire or take medicine for the rest of your life or have surgery.

“So it made a lot of difference. And Robin’s data was so powerful that anybody who then tried to check it for themselves would get exactly the same results. They said it’s true.”

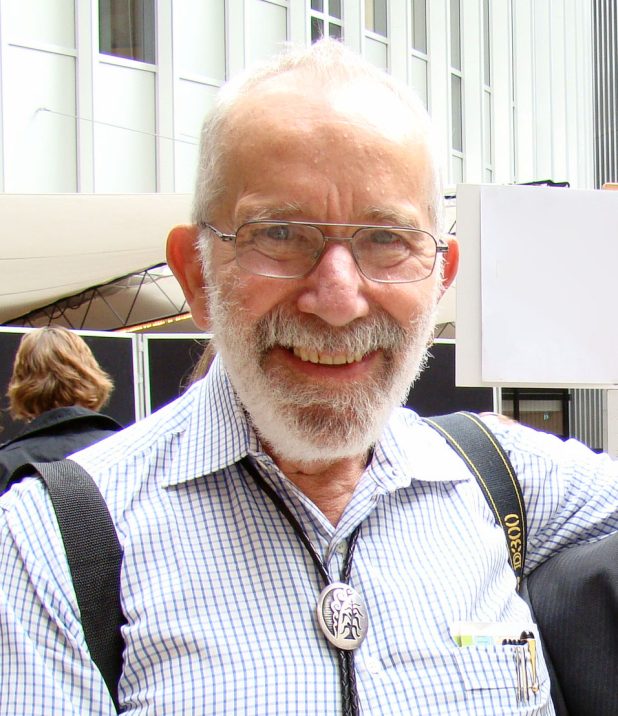

Professor Marshall said Professor Warren was a deeply committed pathologist who was “quite obsessional” about attention to detail, especially when it came to examining samples under the microscope.

He was also a talented artist and photographer, and some of their papers had included his own hand line drawings in them.

Professor Marshall said he hoped their legacy would inspire other researchers to follow their instincts regardless of popular opinions.

“I want to encourage people in research,” he said.

“It doesn’t have to have a useful purpose. If it’s interesting and you like to do it, well, that’s good enough. Get some data, get your PhD or whatever, and you don’t know where it’s going to lead.

“Maybe at least half of the Nobel Prize winners just started off with something like that.”

Photographs supplied by the University of Western Australia